For decades, cycling in America has struggled to roll beyond the pitifully small number of cyclists who ride on a regular basis. Despite the facts that regular riding can slash your transportation costs, improve your health and longevity (cyclists live 2-5 years longer than non-cyclists) and reduce infrastructure expenses for cities and towns, cycling remains a backseat activity for most people.

For decades, cycling in America has struggled to roll beyond the pitifully small number of cyclists who ride on a regular basis. Despite the facts that regular riding can slash your transportation costs, improve your health and longevity (cyclists live 2-5 years longer than non-cyclists) and reduce infrastructure expenses for cities and towns, cycling remains a backseat activity for most people.

There are many reasons cyclists want to see more of us on the road. Some for perceived safety reasons -- citing studies showing that the more cyclists there are on the road, the safer it becomes for all cyclists. Some because a larger cycling population means that more funding will be allocated to cycling-specific infrastructure. Some wish to see cycling increase because of its undeniable environmental, economic, and health benefits.

Certainly, there are areas showing cycling growth. New York, San Francisco, Portland, Denver and a few other cities have seen a rather dramatic upsurge in the use of bicycles on a daily basis for commuting and running errands. But outside of the urban environment's hip pocket, there's not a lot happening.

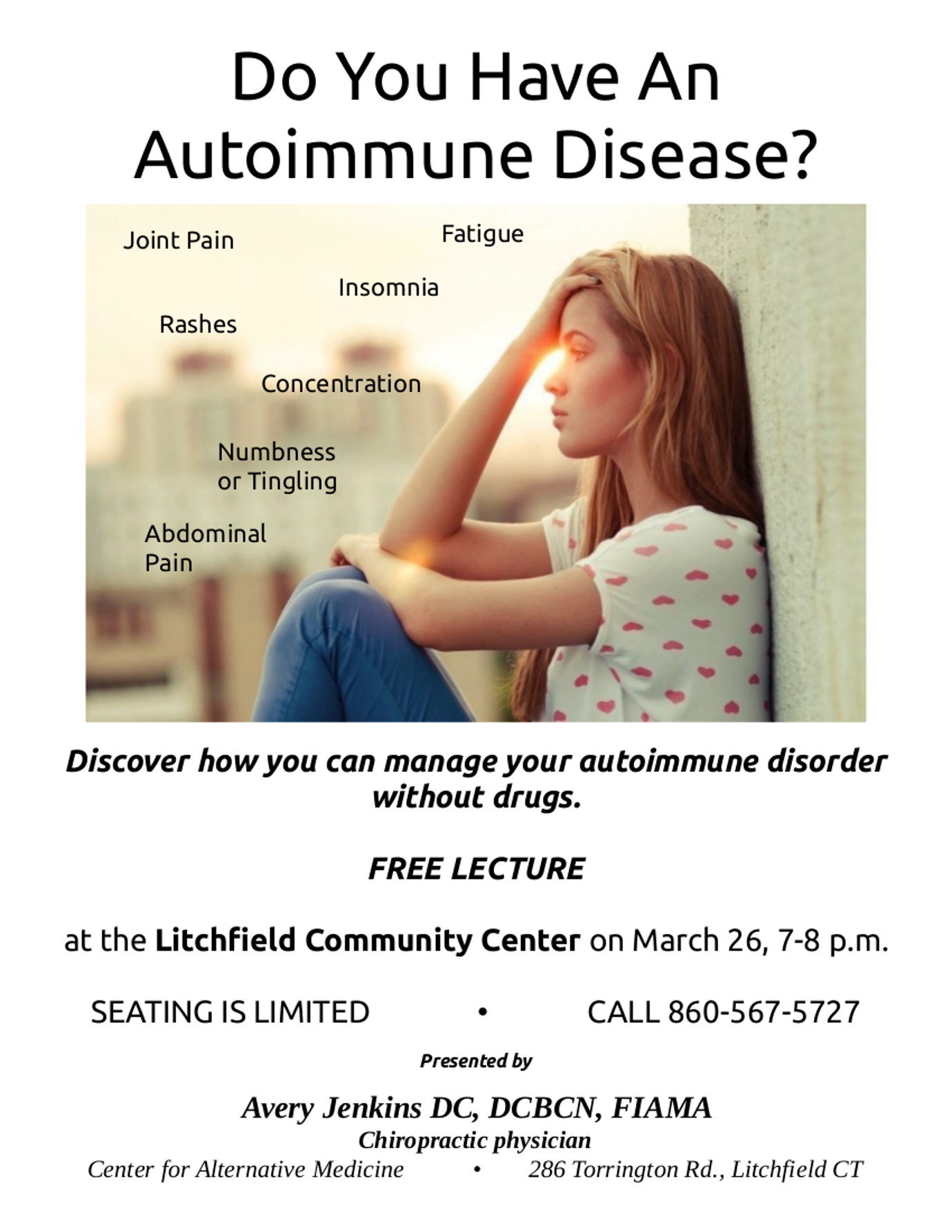

Take Litchfield, for example. I can count on one hand the number of people I've seen in Litchfield using their bicycle as anything more than a recreational device. There are maybe 2-3 people, in a town of 8,000 who commute by bike, and I have never, ever seen another bicycle parked in front of Stop and Shop, CVS, or along West Street.

Is it unfeasible to use a bicycle for transportation in Litchfield's suburban/rural environment? Certainly not. If you live in much of Litchfield, you are, by definition, within only a few miles of the town's center. The town's facilities and shops are also within easy cycling distance of parts of Bantam. I am quite willing to concede that cycling from Northfield, however, may be an uphill slog that fewer are willing to do.

Geography is not the problem. So what is?

There's certainly interest in the state of cycling in Litchfield. There is an active group shepherding a recalcitrant multi-use path into existence. Once completed, this path would connect the center of Litchfield with Bantam, allowing cyclists to avoid Route 202 .

And I confess to being both surprised and dismayed at a few bicycle advocacy meetings I attended in the past couple of years. I was surprised in that the turnout for both meetings, to discuss ways to improve the state of cycling in Litchfield, was significantly higher than I thought it would be . My dismay stemmed from the fact in that I was the only attendee who actually rode a bicycle to the meetings.

Just so that it doesn't slide by, let me repeat that: I was the only person to ride a bicycle to attend two bicycle advocacy meetings.

There's something so dismally wrong with that fact that I have been a little bit afraid to do anything but squint at it sideways for fear of what I might find. At least I was, until I realized that this problem isn't a local one. It's a national one. It's a problem that has infected every cycling advocacy program in the U.S., and it has remained largely ignored:

The problem with cycle advocacy lies at the feet of cyclists themselves and the cycling industry in North America.

The problem is that cyclists need to grow up.

I have been involved deeply in cycling since my teens, when I built my first "10-speed" from junked parts at age 17, to my twenties, when I discovered the joys of recumbent bicycles, to today, as one of the League of American Bicyclist's 3,000+ certified cycling instructors. But while I have grown up with cycling culture, the cycling culture hasn't grown up with me.

Looking back to the cycling renaissance of the 70s, even though it was stirred by gasoline shortages and skyrocketing prices, the appearance and culture of cycling was completely built around the sport of cycling. Movies such as Breaking Away personified the cycling zeitgeist of the 70s.

Fast forward with me through the next 25 years. The next current that dragged cycling again into the public eye was a man by the name of Lance Armstrong. America loves a winner, particularly a winner in a sport dominated by Europeans, who even after 200+ years of independence from the UK, still make us insecure. Armstrong's winning streak, it was thought by many in the cycling community, would bring a flood of riders onto the road. This, of course, was long before we discovered that Armstrong was drugged to the gills and winning more by pharmaceutical fiat than by true talent.

Regardless, the projected jump in numbers never materialized. Sure, there were a few more cyclists on the road than there were before, but hardly enough to make a statistical difference.

Jump to today, and once again, economic conditions have conspired to make cycling a potentially valuable mode of transportation. In fact, it just makes raw common sense to hop on a bike instead of in a car. Without even trying, I saved $3,000 last year by riding a bike a lot of places instead of taking an automobile. Do you have enough spare change to throw away a cool three grand for no reason? I don't. And it's not like I'm some sort of athlete. I'm just a guy on a bike going to work or the store.

And while a few isolated parts of the country have seen a substantial uptick, the seeds of cycling elsewhere in the country have not only failed to blossom, they haven't even taken root (e.g., Litchfield). In many countries of Europe, everyday cycling is becoming a reality as it did long ago for the citizens of the Netherlands, where 86% of the residents hop on their bikes daily to run errands or go to work.

The difference between there and here, and then and now, is the behaviour of the cyclists themselves. Watch, for a few seconds, the cyclists of Copenhagen:

http://youtu.be/xsDxOx7PUP0

What do you see? The first thing I'll bet most people saw was the lack of helmets. Then there is the clothing -- everybody seems to be wearing everyday work or casual clothing. Then there is the behavior, on the part of both motorists and cyclists. The bikes look comfortable, and nobody is bent double in an uncomfortable, pseudo-aerodynamic position. Racks for groceries, briefcases, kids. Everything in that video speaks to what it is like to cycle in a mature cycling culture. Safe. Family-friendly. Gentle.

Compare that to what you've seen of cyclists in the U.S.: Cycling helmets, hi-viz gear, running red lights, running stop signs, making left turns from the right-hand side of the road, riding on sidewalks. Crouched down on uncomfortable-looking bikes stripped down to virtually nothing. Pounding their way to the next stop light. Cycling in the U.S. is almost the converse of cycling in a bicycle-rich environment.

In a cycling-rich environment, the cyclists behave as if cycling is a normal activity. They wear normal clothes. They don't bother with unnecessary safety gear, like hi-viz jackets or helmets. They don't ride like they are pretending to be racing. They ride like -- well, they ride like normal people on a bike. Cycling is the normal way of life.

American cycling, unfortunately, is stuck in the unprofitable, dead-end rut of promoting cycling only as a sport, not as a lifestyle. From manufacturers to advocacy groups, the vision of cycling in the U.S. is still built around the young, macho cyclist forging his way through danger and adversity.

But if you really want cycling to grow, you have to abandon that shrinking demographic. You have to attract different people to the activity, and in particular, you need to make it appealing to women. The percentage of female cyclists is closely correlated with the growth of cycling in a number of countries, to the extent where women cyclists are considered the canaries in the coal mine. When their numbers drop, cycling dies.

So here are the steps cyclists need to take to ensure the growth of the activity.

1. Stop selling fear. Selling an activity as risky and adventurous works very well on the 14-28 male demographic. It doesn't work so well with women, whose number one reason for not cycling more is that they feel it is unsafe. And why wouldn't they? All of this special safety gear that you allegedly need to ride a bike practically screams DANGER!

The fact of the matter is, cycling is one of the safest activities you can engage in. Injuries requiring medical intervention are relatively rare for cyclists, and those who do suffer injury are not infrequently riding unsafely. The alleged danger of cycling has been highlighted by the focus on racing and exaggerated by an industry focused on selling to their slender demographic.

So, for crying out loud, quit preaching helmets. They aren't necessary and you won't die riding without one. Anyone who has thoroughly examined the literature will reach the conclusion that helmets can do little to protect you against serious injury. So if you want to wear one, wear one. If you don't, don't.

On virtually any ride that I encounter a large number of other cyclists, I am bound to get at least one comment about my lack of helmet. And, invariably -- I know, because I have made it a point to track them -- the people who castigate my bareheadedness proceed to run the next red light or blow through the next stop sign. Which brings me to point number 2:

2. Start riding like adults. Motorists don't respect cyclists, in part, because most cyclists ride like children. The majority of cyclists treat the rules of the road as if compliance was voluntary, not mandatory. It ends up making cyclists look like self-absorbed children, and who wants to be like that? If cyclists start to behave in a manner that makes them look like adults, then it is much more likely that other adults will find the activity interesting. And while we're talking about looks...

3. Save the spandex for when you need it. I agree that when I'm on a long ride on a hot day, cycling-specific clothing makes cycling more pleasurable. But that same apparel drives potential cyclists away in droves. There is nobody on the planet Earth who has not looked at a pair of Lycra shorts and said to themselves "There's no way in hell I'm gonna look good in that."

Trust me, I don't. So, unless it's a longer ride or the weather forces my hand, I don't wear cycling-specific clothing. When I'm going to work in favorable weather, I'm in dress slacks, shirt and often my tie. To the grocery store? It's shorts or jeans and a comfortable shirt and jacket. Remember those Copenhagen cyclists in the video? They're looking pretty fly. In fact, there's a whole website, called Copenhagen Chic, dedicated to the classy men and women cyclists of that city.

4. Be nice to others. In pursuit of the macho road warrior image, most cyclists speed down the road, looks of determination set on their faces, ignoring walkers and runners alike. You want more people to ride bikes? Say hi to the runner that you pass. Wave to the kid on the sidewalk. Slow down to just a few miles per hour when you're on the path and passing pedestrians. It's called being nice, and it works phenomenally well, if you want to encourage others to join you.

5. Tell industry leaders to embrace the reality of a mature, cycling rich culture. I've been a member of the League of American Bicyclists for years. As part of that membership, I receive a complimentary subscription to Bicycling magazine. It is the largest cycling magazine in the country. It is also one of the worst. It depicts cycling in all of the immature stereotypes that restrict its growth. Far better would be a complimentary subscription to a magazine like Bicycle Times, which is a far more adult publication.

Similarly, what few audio/video media outlets that cover cycling need to change their focus. Podcasts such as David Bernstein's The Fredcast need to shift gears into a format less racing-centered and more about the cycling lifestyle. While I admire David and his revolving crew of participants on both The Fredcast and The Spokesmen, I began to lose interest when his coverage of Armstrong's fall and its effect on cycling dominated episode after episode, while topics of real meaning to cyclists, such as funding, politics and other news was virtually ignored.

It all comes down to this. If we want cycling to grow beyond its small, homogeneous niche, all of us cyclists need to change our behavior to reflect the cycling culture that we want to bring about. In other words, if you want an environment where most of the population rides a bike -- then you should ride your bike as you would in that environment.

In a

In a  This is the most common reason I hear from people who otherwise might take my advice, dust off their bikes, and go for a spin.

This is the most common reason I hear from people who otherwise might take my advice, dust off their bikes, and go for a spin. In today's installment of Bicycle Month posts, I am going to ever-so-briefly mutate from being a physician and bon vivant to (very) amateur historian.

In today's installment of Bicycle Month posts, I am going to ever-so-briefly mutate from being a physician and bon vivant to (very) amateur historian.