HOUSTON, WE HAVE A PROBLEM. As race day approaches, Dr. Jenkins makes a near-fatal tactical error.

Deep in the woods, a chiropractor encounters a bear! You won't believe what happens next!

Summer has started, and in my neck of the woods, that means Facebook feeds, email lists, blogs and news programs will be filled with warnings and means to ward yourself from the dangers of the outdoors.

In Connecticut, the snow had not even properly melted off my front lawn before we were subjected to dire warnings about a new superdisease being carried by the region's ticks. Nevermind that this disease has been around for a hundred years, and that there have been only 10 cases of it in the past 50 years. No, this is the bug that will sneak into your bloodstream and kill you if you have the temerity to, you know, walk on the grass or something.

Summer has started, and in my neck of the woods, that means Facebook feeds, email lists, blogs and news programs will be filled with warnings and means to ward yourself from the dangers of the outdoors.

In Connecticut, the snow had not even properly melted off my front lawn before we were subjected to dire warnings about a new superdisease being carried by the region's ticks. Nevermind that this disease has been around for a hundred years, and that there have been only 10 cases of it in the past 50 years. No, this is the bug that will sneak into your bloodstream and kill you if you have the temerity to, you know, walk on the grass or something.

Recently, my Facebook feed was briefly overcome by a surge of posts reminding us of the horrible dangers of Lyme-bearing ticks and how to protect yourself from them (naturally, of course). Thank goodness the extra-virgin olive oil "trick" hasn't resurfaced yet. I'm pretty sure that was both messy and expensive for anyone who tried it.

The other day, I inadvertently horrified a couple of patients of mine when I was telling them about my exciting weekend with a like-minded group of treehuggers, camping in the field, chucking spears, and generally having an all-around good time.

My patients asked me what I used to keep the ticks off me. I said, "Nothing, really. Just did a tick check when I got home."

They looked at me like I had told them I was planning to step outside the airlock with a monkey wrench and no space suit to repair the solar panels. They were incredulous. "You didn't use anything?" they asked. Clearly, their estimation of my intelligence had just plummeted, and my abilities as a man of healing were questionable.

But it's not just the creepy-crawlies that get no love. Any intrusion of nature into our carefully-ordered world seems to be cause for anxiety.

When I put up a bird feeder on the lawn of the Center recently, and posted a picture of it online, virtually every response I received was a warning about how the bears would shred it in short order, and that I should take it down now -- NOW!! -- before the Attack of the Claws began.

In the interests of journalistic honesty, I'm going to confess right now that I'm a big bear fan. I've had many an encounter with these creatures, in the wild and in my backyard, and never seen much reason to worry, so long as nobody forgot their manners.

My Affair with the Bear began in the Dark Ages (musically speaking, at least) of the 1980s, when I was backpacking through a particularly isolated stretch of trail in Maine. I had already gone several days without seeing another human, and expected to go a few more in similarly inhuman bliss.

That morning was a pleasant lowland walk among 100-year-old pines, whose needles littered the ground and made the trail feel like a composite running track. I had stopped to take off my pack, swill down some water, and just absorb the beauty for a minute.

Standing there, I heard crunching in the bushes, and spotted an enormous black bear meandering through the undergrowth. I stood there, unmoving, as he wandered innocently closer. I was downwind, absolutely still, and he wasn't expecting any company.

As his path prepared to cross mine, I realized this was the photo op of a lifetime. Ever so slowly, I reached down to my pack and unslung my weighty 35mm SLR camera. He still didn't see me, bears being somewhat nearsighted.

But when I unsnapped the cover, the bear heard it, spotting me in a second.

And then the impossible happened.

From a distance of no more than 20 feet, I stared into the bears' eyes, and he into mine. And I was lost in his presence. I felt that bear, and in him there was nothing resembling humanity. His entire being was wild, feral and fierce and something indescribable in human terms. There was no emotion. Everything was now. Everything was present. Everything was.

And though it felt like an hour, it could only have been a few seconds before I clicked back into a sense of myself, and was once again a man staring at a bear in a forest hundreds of years old and empty of other humans.

I began to rationally consider my options. In my previous encounters with bears, I had simply made some loud noises -- yelled at them, or banged some camp pots -- to scare them off. But he was far too close for that, and he may take that as aggression. I knew I didn't want to piss this bear off.

Running away would be absurd. He would take that as fear, and with a short sprint would be on top of me to take a closer look at this puny, hairless, scared animal.

So, I arrived at the only option possible.

I opened my mouth.

And I said, "Well, good morning, Mr. Bear!"

He didn't give me a chance to invite him to breakfast. In the blink of an eye, he was gone, racing through the ancient woods in a sprint that took him out of my range in seconds.

Since that time, I've never been very disconcerted by bears. A couple of years ago, I came home from work at lunchtime, and found a bear sitting at the bottom of my shared driveway, with the neighbor's trash can in his lap, scooping out melted ice cream.

I looked at him, he at me, I reminded him to clean up after himself, and went inside for lunch.

So when the dire warnings about the imminent demise of my birdfeeder at the hands of nasty bears came pouring in, I was somewhat nonplussed.

I mean, really, who *wouldn't* want a bear in their backyard? Though I would wish that if they did decimate the feeder, they leave a few coins for a replacement.

The warnings, as I suspected, were overwrought. The bird feeder still stands, unmolested, and has brought a number of interesting and beautiful birds to my office.

I have no doubt that shortly we'll be hearing dire predictions of some new near-malaria being carried by mosquitos and the public health risk of bird poop on your car. Not to mention the sure death that will result from sun exposure without being slathered with sunblock.

As a doctor who is concerned with public health, I ought to be bringing these warnings to my patients. But I'm not and I won't, because these are, in fact, anti-health messages.

I want my patients to go outside, get plenty of sun exposure without toxins seeping into their skins. I want them to get dirty, and come eye-to-eye with a nature that we have been taught to fear. This is what will make them healthier, physically and mentally.

You see, when it comes to health, there is no "I." There is only "We." As individuals, we exist in a virtual bath of microbes. There are more bacteria in our guts than cells in our bodies; with each breath we inhale a cloud of organisms. Each time our feet touch the earth, we literally touch millions of other lives.

The same is true on a larger scale. Without the bees, our food supplies would rapidly collapse. Species of plants and insects manage one another, the knowledge which our agrarian ancestors used to their advantage, but we have poorly replaced with simple poisons. Psychologically, we cannot exist without one another, which is why solitary confinement is one of the most effective tortures we inflict on one another.

Thus, the more divorced our food supply becomes from the environment in which it should exist (I shudder at the thought of cloned meat, grown in a lab), the less effective it is, not only in providing nutrients, but in protecting us from disease.

And the more we seek to isolate ourselves from our environment, from the nightmare bears of our imagination, the sicker we make ourselves. Without a healthy intestinal microbiome, we fall ill. Without regular exposure to soil, our immune systems become dysfunctional. Without regular exposure to the sun, the wind, and the rain -- the very environment that millions of years of evolution has primed us to inhabit -- we fall victim to the diseases that we run from.

So take this doctor's advice. Ignore all of the "public health" warnings that will come your way this season, seeking you to herd you away from the alleged dangers of nature. Do your health a favor. Turn a blind ear to the fearmongers. Walk through fields without fear of imminent illness and invite all of nature into your backyard. You will be healthier for it.

This religion is the greatest threat to Western society.

Forget ISIS. Forget the Taliban. Forget Quiverfull. There's a new extremist religion that is permeating our society, and its tendrils are reaching to the highest levels in our government. You won't hear its adherents uttering the name of their religion, but it has all of the characteristics of a religious cult. It has leaders who are idolized and whose pronouncements dare not be questioned. Similarly, it requires that all of its adherents believe in the exact same dogma. Any variation from the accepted "truth" results in excommunication, shunning, and economic ruin.

At the same time, this religion engages in barbaric practices, including the ritual torture and murder of animals. Some of its temples have their own standing armies.

If you're not worried yet, you should be, because this religion is increasingly controlling public discourse in this country, using astroturf groups and social media to limit debate and control thought.

This religion? It's called Scientism. And it is doing far more damage to our country and our society than Muslim extremists ever will.

Scientism is the belief that the methods of science are the only appropriate means of inquiry about the universe, and that only its conclusions are valid. While its practitioners usually claim they are practicing "science" (the methodology) rather than "science" the religion, most of the educated masses in the West are, in fact, believers in scientism.

The priests of scientism are, of course, the scientists. Like any priest, he or she wears traditional garb that identifies him as a member of the exalted class -- the lab coat -- and is accompanied by various instruments of office, depending on their sect. Philosopher Ivan Illich has pointed out that the medical priest, for example, often wears a stethoscope around his neck that identifies him as a member of the exalted. Others may be accompanied by various forms of obscure computing devices or, increasingly, wearable tech.

Their temples are windowless, climate-controlled, artificial environments with guarded entries to keep out the hoi polloi, because they surely could not understand the arcane rites within and would likely confound its rituals. Their temples also serve to wall out the wider world with its chaotic processes and systems so exceedingly complex that they still overwhelm the Scientist's wards of office.

In one respect, at least, they are correct -- I doubt that the common man would understand the Very Important Reasons for keeping sentient animals in five point restraints with their skulls exposed, under constant torture until they die, all so that we can better understand the Supreme Knowledge, to use but one example of the excesses of this religion.

What Scientism's practitioners have forgotten is that science is a tool, not a belief system, one tool among many which mankind can use to understand and organize the world. And science is a spectacularly useful tool, that should not be denied. None of you reading this blog does not benefit almost every second of every day from the fruits of scientific investigation.

Yet the true believers go too far. As scientist Austin Hughes has written about his profession, "The temptation to overreach, however, seems increasingly indulged today in discussions about science. Both in the work of professional philosophers and in popular writings by natural scientists, it is frequently claimed that natural science does or soon will constitute the entire domain of truth. And this attitude is becoming more widespread among scientists themselves. All too many of my contemporaries in science have accepted without question the hype that suggests that an advanced degree in some area of natural science confers the ability to pontificate wisely on any and all subjects." (Hughes, Austin L. "The Folly of Scientism." The New Atlantis. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 Feb. 2015.)

But like all tools, science must be guided by morals, ethics and systems of constraint that are not part of its own organization. However, that does not exist today. While there are boards of ethics which presumably oversee some research, all of these boards consist of practitioners of Scientism themselves, either as lay members of the church, or as clergy. That's exactly the same as having the Catholic church investigate its priests in claims of pedophelia, and the results in Scientism have been just about what you would expect.

Scientism now invades our public discourse on matters of great importance. Take, for example, the recent controversy regarding vaccination policy. The pro-vaccination camp immediately claimed the high ground of alleged scientific legitimacy, accusing all naysayers of being "anti-science." Now identified as heretics, those questioning current vaccination policy were considered fair game for all of the usual behavior-control tactics available to religion: Shaming, shunning, accusations of other-worship -- in other words, the exact same techniques used by all extremist religionists to eliminate dissent.

What got lost in the astroturfed "debate" was a nuanced and critical examination of what the research actually does say about the risks and benefits of vaccines -- something which varies from vaccine to vaccine, and is not the monolithic single risk/benefit equation that the pro-vaccination camp tries to glue over a much more topographical research landscape. They don't want you to see that their gods don't always agree.

The need to adhere to established doctrine does not just apply to the populace at large, however. It applies even more strictly to the acolytes and junior priesthood, who lose jobs and careers if they dare to question the recieved wisdom of institutional science.

Even those with established bona fides are not secure from the tyranny of scientific zealots. You saw it with Linus Pauling, as he explored the concepts of orthomolecular therapy before that discussion could be controlled by the pharmaceutical companies. Or, to cite a more recent example, Rupert Sheldrake's banned TED talk and his ongoing excommunication for having the temerity to advance a research-based hypothesis of vitalism.

Scientism presents a danger on many fronts, not only in its ability to frame public policy debate in ways which force a predetermined income but, more importantly, by controlling the nature of scientific inquiry itself. The rate and direction of scientific advance is entirely dependent on the questions scientists ask. The more that these questions are restricted to only support the status quo, the less progress will be made, eventually turning the focus of science so inward on itself that the entire charade of "advance" collapses.

Perhaps that will be a good thing. At that point, we as a society will become more free to choose the best lenses through which we view the world, and in so doing, escape the tyranny of materialistic rationality -- a tyranny which has as its only goals the elimination of self-determination, quashing of educated discourse, and invalidation of the richness of individual experience.

Being up front about things.

It is often overlooked by doctors, but the person sitting at the front desk is perhaps the most important person in the practice. She is the first voice that a new patient hears when they call and the first face they see when they walk in the door. If a patient doesn’t like her, or she is rude, or incompetent, it is very likely that the patient will leave unsatisfied with their care. In this, my 20th year of service to Litchfield County, I will occasionally be writing posts looking back at the history of my practice, and I’m going to start where most of the action happens: Up front.

It’s not always been a pretty picture. After all, I’m a doctor, not an HR specialist, and I’ve made a few hiring mistakes. In fact, one of my best friends, who is a big wheel in executive employment and the founder of what is now a multi-million dollar placement firm, once said to me, “Avery, do you know how I’ve managed to be so successful? All I have to do with a hiring problem is think to myself, ‘how would Avery handle this?’ and then do the exact opposite.”

Hmmph. Granted, my hiring process is perhaps not the best, but I have learned a thing or two over the years.

After opening my practice in Kent, CT, I was not initially busy enough to need someone at the front desk. The phone did not ring all that often and the two treatment rooms I had were more than sufficient. Within about six months, though, trade was brisk enough to require a hired hand, at least a few times a week.

This was long before the Great Recession, and, in fact, was during a boom part of Kent’s oft-anemic business cycle. So good help was hard to find.

But I got lucky. Through a colleague, I found out about a young woman, single mother, who was going to school part time in accounting, and looking for work. Bingo.

I immediately hired J., and she stayed with the practice for several years, until she graduated from college. Her daughter was just a baby, and during those early (and rather slow) years, J. would bring her daughter into work, and set up a playpen in one of the treatment rooms, where the baby would nap and occasionally yell for her mother. It was a situation that worked out well. J. was young, intelligent, and of course, could whip numbers around in her sleep, so my accounting and billing was always up to snuff.

It didn’t hurt that J. was cute and friendly, so the patients really liked her as well.

I didn’t know it at the time, but during those first few years, J. and I were putting into place procedures that have lasted until this very day. It’s interesting that even now, when I’m faffing about the file room looking for some ancient document, I will find a file labeled in her handwriting, under a filing system she developed and that has only been built upon by her successors.

Of course, as soon as she graduated, she was snapped up by Mighty Big Corporation, and went to work full time on a salary almost equal to my own at the time.

At this point, I started on a personnel cycle that has seemed to repeat itself periodically.

After J.’s departure, I went through a bit of a merry-go-round with staff. There was the 30-year-old redhead who was moonlighting as a dominatrix. Then there was the ex-postal worker with authority issues. Neither of those lasted more than a few months, which is when I hired my First Big Mistake.

She lasted several years, and there seemed to be nothing wrong with FBM. She had a great personality, patients loved her, and she exuded competence. It seemed that I had made a great hire, initially. And for the majority of the time she worked for me, it seemed like she had great control over the financial end of the business.

Unfortunately, as I found out later, she was also moonlighting. In this case, however, she was moonlighting for my competition, and doing it when I thought she was actually working in my office. She also called to quit -- to go to work full time for the competition -- when I was out west dealing with a terminally ill family member. That wasn’t a good time. Also, the billing had kind of gone to hell in a handbasket while she moonlighted while I imagined her being at my front desk.

Once again, I found myself on the staffing merry-go-round. There was the woman who interviewed great, looked great on paper, and had hand tremors. By the second day, the tremors disappeared, and by the second week, a couple of patients had complained about the smell of alcohol. Meanwhile, she was telling me how she had taken to falling asleep at night in her front yard.

She was replaced by the top-of-her-class college graduate, who oddly enough, had been unable to find any employment. It didn’t take long to discover why. For the two weeks she worked for me, she actually only came in for two days. On her final day of “work,” she called in with yet another excuse for not showing up, and I told her not to bother at all, that she was fired.

She started shouting at me, about how dare I fire her, and it was so unfair, and she was doing her best...she was outraged that she was being fired from a job that she hadn’t really shown up for.

This is what gives the younger generation a bad name.

There was also the woman I hired who came for her first day of training. After training all morning, she went out for lunch, whereupon she called me and quit. She didn’t even want to come back for a paycheck.

But, about this time, T. agreed to start working for me more-or-less full time. I had initially hired T. only for Saturday morning hours. She was actually perfect for the job, working weekdays as a bookkeeper, and possessed of a warm and outgoing personality. I finally convinced her that she was working for a dead-end firm, and she signed up for the ride with the Center for Alternative Medicine.

And what a ride it was! T. worked for me for over a decade (I said 13 years, she said 12, so I concluded that maybe it was only 12, it just felt longer), through phenomenal change. During that time, I introduced acupuncture and nutrition into my practice, bought a building, closed the Kent office and moved the whole kit and caboodle to Litchfield.

The thing about this type of job is that you work cheek-to-jowl with one another, and so fundamentally, your personalities have to match. T. and I worked well together, so much so that very frequently patients asked if we were married. To which T.’s response was usually something along the lines of “I’d rather shoot myself first.”

That was the nature of our relationship, and over the years it got to be a habit for me to gauge the success of any day at work by whether or not I was able to get T. to say “I hate you!” to me. A truly successful day was “I hate you!” followed immediately by “I quit.”

Which was all fun and games of course, until the day she came in and said “I quit” and really meant it. There was no discord or ill-will. She had simply tired of the job, and found one with better benefits and more suited to her current needs. T. left on good terms, and left an impression on the practice that has dimmed little with time. Patients will still ask me about her and how she is doing.

You get the story by now. T. was followed by a couple of unsuitable candidates, one of whom informed me shortly after taking the job that she considered me working for me to be probationary, and then was wholly excised when she was terminated after herself going AWOL.

That was followed by Second Big Mistake. SBM similarly had me under the impression that all was under control, while the cart was careening wildly down the mountain. Once again, I only discovered the condition of things after she left.

While I’m still paying the cost of SBM’s duplicity, the bright side of that stormy cloud was that SBM’s employment convinced me to restructure the practice. Part of the problem was that the front desk job had just grown too large. So I split one job into three, and have put checks into place that help me independently spot problems before they become too large. This has also enabled me to hire people who are specialists in each discipline, which has resulted in even better performance.

Again, after a bit of faffing about, I hired G., who is -- at least at the time of this writing -- sitting at the front desk. G. represents a bit of a change, and is reflective of my new thinking about what the front desk job entails and where I want to take this practice in the next 15 years.

G. actually got hired because of something my big-pooba HR friend had said. “Avery,” he said, “you need someone who really wants that job.”

That was G. Although G. was young and untried, she was hungry. She had the basic skills I needed and, more importantly, I felt her to be fundamentally honest. She also had -- there’s no other way to put this -- attitude. I’ve been doing this for two decades, and the practice at this point needed an injection of passion and energy. G.’s got that.

Something else that she brings, which has been missing ever since T.’s departure, is an abundance of laughter. The other day, one of my patients said to me, “You know why I like coming here, Dr. J?”

I was somewhat hoping that he would mention my phenomenal diagnostic skills, or my skillful touch with hand, herb or needle.

Nope. “I like it here because there’s so much laughter,” he said. “You go to other doctor’s offices, it feels like walking into a graveyard. But not here.”

The incident that made me feel best about hiring G. happened just a few weeks into her employment. I was asking her to do something, and explaining how to do it, and explaining how I should have done it, but hadn’t had the time to. She just cut me off in mid-explanation, looked at me with a serious expression, and said “Don’t worry. I got your back.”

She did, too, fixing my mistake with efficiency and aplomb.

After 20 years in this game, and, as I’ve been told, “more receptionists than Seinfeld had girlfriends,” it’s good to know that once again, somebody’s got my back.

The future's so bright, I gotta wear shades.

I feel a bit like Janus today. He was the Roman god of transitions; usually depicted with two faces, one looking forward and one looking back, Janus stands at the crossroads of our lives, guiding our passages from where we are to where we shall be. Today, I look back on what, in 2015, becomes two decades of private practice, and where I will be going in the future. So for a moment or two, Janus I shall be. 2014 was a year full of new beginnings for me, both personally and professionally. I’ve made a great many new friends, and enjoyed a renewal of both intellect and spirit. It was also the year I rediscovered my voice, as my writing -- once my career -- has again begun to flourish, not only publishing on my blog, but also at other sites such as the Good Men Project. My book has been resurrected, and is finally making steady progress.

The Center for Alternative Medicine, my practice in Litchfield, also saw an incredible amount of expansion in 2014. I introduced my private line of supplements for general health, assisting people with chronic diseases, and to support mental health issues such as anxiety and depression. This, along with my ability to create custom herbal formulas for patients, has fulfilled a life-long dream of mine; the ability to incorporate my knowledge, not only into the recommendation or use of herbs and nutrition, but in their creation. This is a wonderful capability that will benefit all of my patients, regardless of whether they are seeing me for physical injuries or internal disorders.

I am the only doctor in Connecticut, to my knowledge, that has ability to offer both of these services. It has taken years of education and experience to reach this point, and my heartfelt thanks goes to all of those people who have helped me get here.

Growth occurred internally, as well. Over the course of this past year, I went from having a single employee to three employees. Though most of my patients don’t see anyone except the person at the front desk, behind the scenes I now have people handling the medical billing as well as bookkeeping and accounts receivable. This rapid growth also had me working hard on administrative issues, developing the policies and procedures that never had to exist before.

The front desk is now in the capable hands of Giselle, whose laughter is infectious and whose efficiency is becoming legendary. The steely-eyed Joanne is facing off with the insurance companies, making sure that they live up to the promises they made to you, my patients. And Thanhien, who has managed million-dollar payrolls in her sleep, is making sure that our cash flow runs evenly. I could not ask for more capable hands to assist me.

As if those weren’t changes enough, I have an ambitious program outlined for the next year, with some entirely new services.

In December, I passed the examination to become a federally certified Medical Examiner, and am now one of only a handful of doctors in Connecticut who offer the medical examinations required every two years for everyone who carries a commercial drivers license. I really enjoy doing these exams, as I get to explore with drivers the wide range of health issues that effect them. I have already uncovered a few serious illnesses during the course of my exam, and helped drivers find appropriate care for them.

I also now have a CLIA-certified laboratory on site, and in partnership with a couple of other laboratories, we can now provide a comprehensive suite of employment and forensic testing services.

I now have the ability to provide breath, urine and hair analysis for drugs of abuse, for everything from alcohol to opiates. When these test results are required for evidence in court, I have the ability to provide what is called “chain of custody” handling, which means that the sample is overseen from collection to analysis, virtually eliminating the possibility of intentional or accidental tampering.

I can also provide a full range of relational DNA testing, including gestational paternal testing. This means that, with a couple of blood samples, I can determine the father of a child even before it has been born, with 99% accuracy. I can also perform non-invasive parental DNA tests, as well as testing for multiple siblings.

My DNA testing, like the drug testing, can be done with chain-of-custody handling for the court or other agencies, or even to support immigration and citizenship claims.

The best thing is that I am making all of these services as affordable as possible for the average person.

Anyone who has picked up a paper in the past few years knows that medical services and products are incredibly expensive and have a huge markup. This is, in part, due to the inefficiencies of the medical system, with huge amounts of overhead.

I, on the other hand, have been a sole practitioner for decades. I know how to keep my overhead low, and as a result, I can offer these services more conveniently and at less cost than anyone else.

Ok, so is that the crop? Let me think...private line nutrition, custom herbs, new staff, DOT exams, drug testing, DNA...yep, I think I covered all the bases.

Oh, yes, except for one thing:

I want to thank every single one of you who helped make 2014 the incredible year it was. My patients, my friends new and old, and my family have given me so much for which I am grateful. I can only hope that I have given back in equal measure. I wish for all of you the most wonderful year to come.

Are You Ready for a REAL Detox?

With 20 years of providing nutritional therapy for patients, I am confident that my 28-day cleanse program is the best system out there in terms of improving your health. While most "detox diets" confuse simple weight loss and "feeling good" with measurable health improvements, I use individualized, objective, quantifiable yardsticks to determine how much we are improving your health, and how to best manage your health concerns over the long-term.

This cleanse is very often the first thing I do with my patients suffering from chronic disorders from allergies to depression.

Beginning Jan 2 through Jan. 9, I will be offering special package pricing for people wanting to begin the road back to health. This will include weekly individual nutritional counseling sessions as well as an educational seminar which you can enjoy at home on your schedule.

Please join me in beginning the new year with the best health you can imagine. Call now to reserve your place in my unique program.

Avery L. Jenkins, DC, DCBCN, FIAMA Board-certified Clinical Nutrition Board-certified Medical Acupuncture

Depression is a Communicable Disease

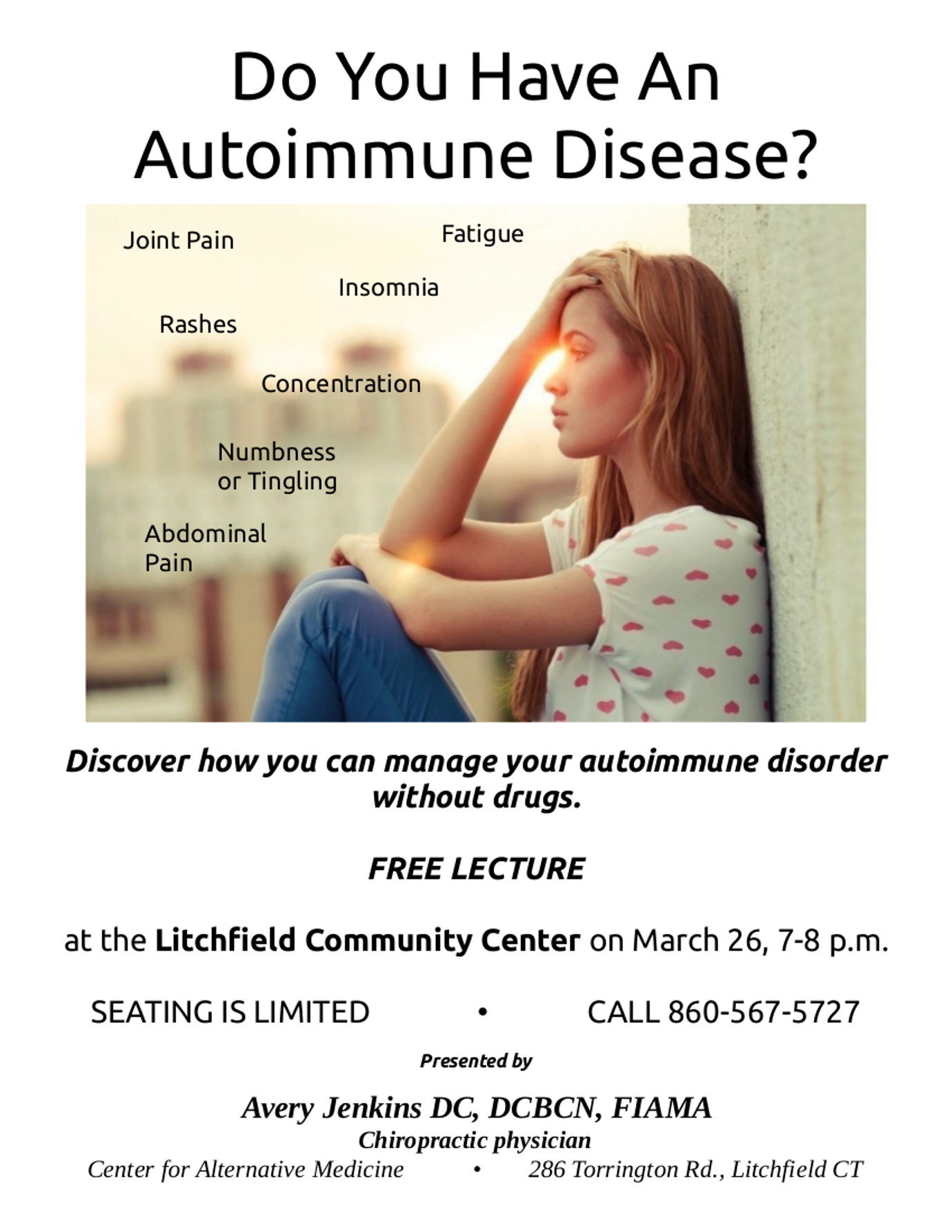

I'm very pleased to announce my first lecture of the fall/winter season, and one that couldn't be more timely.

With all of the concern circulating about new infectious diseases, there is one communicable disease that is rarely seen for what it is: Depression.

I'm very pleased to announce my first lecture of the fall/winter season, and one that couldn't be more timely.

With all of the concern circulating about new infectious diseases, there is one communicable disease that is rarely seen for what it is: Depression.

Please join me on Wednesday, Nov. 5, as I present new information which shows that depression is much more than a simple neurotransmitter imbalance in the brain.

Research is now showing how depression can be transmitted among members of a community, or even between people separated by great geographical distance.

The problem is not all in your head. Depression can result from engaging in certain activities, eating certain foods, and even by the microbes in your gut.

Find out how you can avoid depression infection, and what to do if you've already caught it, at my free lecture. Bring a friend.

Depression is a Communicable Disease

FREE

Litchfield Community Center

7 p.m., Wednesday Nov. 5

Seating is limited, so please call 860-567-5727 to reserve your place today!

The Book of Invasions reaches the New World

Wisp of a Thing: A Novel of the Tufa by Alex Bledsoe

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Wisp of a Thing: A Novel of the Tufa by Alex Bledsoe

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

This is a novel which, like its characters, possesses depths that it does not reveal readily to the casual reader. On the surface, this is a straightforward fantasy/adventure novel that is utterly enjoyable in and of itself. The characters are interesting, the pacing is good, there are plenty of surprises, and like its predecessor, The Hum and the Shiver, it draws to an exciting and satisfying climax. I read The Hum and the Shiver in a single day, and, as I promised myself, I extended my time with Wisp of a Thing to three days, not because it did not entice, but because I knew I would have to wait many months for the trilogy's final book to appear, and I wanted to postpone that bleak horizon. On this basis alone, I award the book 5 stars.

At the next level, however, this is a book about the power of words and of song. The protagonist, Rob Quillen, is driven to find the words and the song that will set his troubled soul at rest, and his search unearths a power that threatens the very fabric of Tufa society. I found the first book of the Tufa series through the songs of the band Tuatha Dea, and now I find that through the second book, I find more music from other artists. The loop from music to book and back to music has already introduced me to artists I would have otherwise never heard. I honestly cannot think of another book that has expanded my horizons in such an unusual way. From Rebecca Hubbard's steampunk aesthetic and unearthly vocals, to the haunting, candlelit performances of Jennifer Goree, my playlist has exploded with a new kind of music that I didn't know I was looking for, but now find I can't do without. Sort of like a visit to Needsville, I suppose.

At yet another level, Bledsoe's tale reaches deeper into our pre-historical consciousness. Bledsoe has taken on the task of retelling the ageless battles and unending intermingling between the Tuatha De Danann and the Formorians, within the uneasy truce that the Tuatha made with the Milesians, when they conceded the material Earth to mortal hands. Bledsoe does not hew as closely to the received wisdom as did David Drake in his retelling of the poetic Edda in his Northworld trilogy, but that should be expected, as the Celtic stories themselves are jumbled, overlapping and contradicting, unlike the Edda.

I won't spoil anybody's fun by revealing the subtle meanings that Bledsoe has stowed away in this book, but I would suggest that anyone reading Wisp of a Thing do their homework if they want to enjoy some of the book's hidden richness. Like the characters in the novel, pay attention to the turning of a leaf or the feel of the wind, and greater understanding will be awarded to you.

The trouble with "middle" books in a series is that they often bog down as the author maneuvers his pieces on the board for the denoument in the final books. Bledsoe deftly avoids this problem; while I have little doubt that all the players are in the right place for the last book of the trilogy, there was no sacrifice to the current story. It kept me on the edge of my seat.

With this book behind me, it will be an empty several months until "Long Black Curl" debuts. I guess the only thing I can do is pull out my banjo and pluck out the songs I hear on the wind.

Coming Home to the Tuatha De Danann

The Hum and the Shiver by Alex Bledsoe

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

The Hum and the Shiver by Alex Bledsoe

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

It's not often -- in fact, it's been years -- since I've read a book in one sitting. Or, rather, several sittings in a single day. But The Hum and the Shiver so enthralled me that I couldn't put it down until I was done.

I sort of backed into this book. A few days ago, I stumbled across this band, Tuatha Dea, who describe their music as celtic tribal gypsy rock. The band's latest album "Tufa Tales: Appalachian Fae" took as its inspiration the series of books of which "The Hum and the Shiver" is the first. I loved the music. I figured how bad could the books be?

This book lives up to the promise of the music, or perhaps for others, it's the other way around. At any rate, this telling of the prodigal daughter's return to her home and her people, and her struggle to reclaim herself, her heritage and reshape her future, is at turns delightful and intriguing. And though it is often difficult for an author to describe the fantastic in a realistic way, Bledsoe handles this task very well.

Bledsoe's evocation of a people hidden away in the Appalachian mountains, maintaining the Old Ways, also rings true to me. I grew up on the edge of Appalachian culture, and I remember as a 16-year-old driving down rutted gravel roads to a barn or a roadhouse with a 6-pack to sit on a picnic bench and listen to awesome banjo picking and guitar playing. This is the world Bledsoe takes as his foundation, and it is not difficult at all for me to see an Americanized Tuatha in such a place.

I enjoyed reading this book immensely, more than any other fiction I've read in years. But I fully intend to take two days, or even three, to read the next book in the series.

The Last Great Walk, by Wayne Curtis -- a review

The Last Great Walk: The True Story of a 1909 Walk from New York to San Francisco, and Why it Matters Today by Wayne Curtis

The Last Great Walk: The True Story of a 1909 Walk from New York to San Francisco, and Why it Matters Today by Wayne Curtis

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Taking as his point of departure a transcontinental walk by a 70-year-old man over 100 years ago, author Wayne Curtis takes us on a spritely, interdisciplinary walk on the subject of walking itself.

"The Last Great Walk" is only roughly built around the 4,000-mile perambulation of Edward Payson Weston, a competitive walker during a time when such athletes possessed the attention given to NBA stars today. Instead of trying to recreate Weston's walk, Curtis wisely dovetails his chronicle of America's last great walk with essays on the biology, sociology, anthropology, neurology and the psychology of walking.

And a fascinating journey it is. Curtis escorts us from the La-Z-Boy museum in Monroe, Michigan to the great walking cities of the world, and from the present into shadowy prehistory where a group of primates discovered the advantages of bipedalism on the savannahs -- and spread across the world on their own two feet.

Along the way, we meet the archenemy of pedestrianism, the automobile, and survey the century-old struggle between these dichotomous forms of transportation.

Even for those of us who have stepped outside the car door and thrown away the keys, the effects -- primarily deleterious -- of the automobile on our society are surprising. For the most part, Curtis takes great pains to prevent his book from becoming just another pedestrian's screed by maintaining an even tone and allowing the facts, and the scientists and researchers who have uncovered those facts, speak for themselves. But there are times when he cannot hold himself back.

"Automobiles are the Plato's caves of the modern world," he writes. "From them we see only shadows, the rough outlines of our existence. The map of this world is drawn with fat, cartoonish markers rather than finely sharpened pencils. The detailed lines of the etchings around us are lost, replaced with hulking shapes whizzing by at sixty miles per hour, vague and often amorphous forms, save for the haunting and startingly blue Best Buy sign and the inquisitive yellow eyebrows of the McDonald's arches jutting over distant rooftops."

Walking, on the other hand, is not only transportation, but "can also be like the best sort of daydreaming, a way to explore without direction. The art of the long, aimless walk was accorded uncommon respect and attention across the Atlantic in the nineteenth century. The flaneurs -- from the French word for "one who strolls" -- filled a strange ecological and cultural niche."

As we journey on these paths, we discover how walking is fundamental to our health by giving us a sense of place and by challenging not just our muscles but also our minds.

"Being lost is an essential human condition....Abandoning the experience of being lost is like losing our facility for empathy; it's a central part of what made us human, the bedrock upon which both mobility and mind were built," Curtis writes.

I came upon this book only a few months after I rediscovered the joys of bipedalism myself, and it provided me with the rational underpinnings to my subjective experiences. I now understand why time seems to dilate for a walker, and why certain paths, though indirect to my destination, are far more appealing to me.

I also understand why life feels so much richer now that I am a walker, rather than a driver. As anyone who has abandoned their car can tell you, life gradually moves from flat 2D to a fuller three dimensions with the more footsteps you put between you and your car. Curtis explains the neurology and psychology behind this experience, and what we have lost, as individuals and societies, as we have abandoned walking.

Yet Curtis always returns to Weston's great walk across a country burgeoning with prosperity and on the cusp of transitioning to a car culture. In doing so, Curtis makes a solid case for a return to our pedestrian roots, and why it makes sense personally, socially and economically to do so. Which is why Weston's walk still matters today.

View all my reviews

From pain and cane to freedom.

I am thrilled.

Early last winter, a patient walked into my office -- barely. She had suffered from intractable back and leg pain for a year, and was, literally, days away from surgery. Her spinal stenosis was killing her. She shuffled with her back permanently bent 35 degrees from vertical. Straightening up was impossible as it would send jolts of pain down her legs. With her head forced downward, she couldn't see very far in front of her. All she could see was the ground and pain.

I am thrilled.

Early last winter, a patient walked into my office -- barely. She had suffered from intractable back and leg pain for a year, and was, literally, days away from surgery. Her spinal stenosis was killing her. She shuffled with her back permanently bent 35 degrees from vertical. Straightening up was impossible as it would send jolts of pain down her legs. With her head forced downward, she couldn't see very far in front of her. All she could see was the ground and pain.

We had some great initial success. After her first visit, she cancelled her surgery. After a couple of months, she got rid of the walker. A little bit longer, and she didn't need a cane. Then she started standing upright, taking walks, and talking about getting off all of the pain medications she had been on.

Throughout her recovery and rehabilitation, she would comment on my trike, which I frequently ride to work in lieu of driving or walking. As it turned out, she had once been an avid cyclist, but her back problems had taken that away from her years ago. As she improved, I suggested the trike as a great way of regaining strength in her muscles without risking falling. She loved the idea, but never quite felt ready for it.

"Maybe one of these days," she would say. I could see in her eyes that she wasn't sure that day would ever come.

With a home rehabilitation plan in place and less need for my oversight and treatment, I discharged her from active care early this summer. Today, she came back to see me for a long-term follow-up.

She was doing well, she said. No pain medications for months, she wasn't in pain, and she couldn't believe the amount of energy that had returned since the heavy-duty painkillers had been eliminated from her system. I could see her eyes were bright, she had a liveliness to her step that hadn't been there before, and the color had returned to her face.

As I concluded the visit, she said there was one other thing I needed to know.

"I bought a trike," she said, grinning ear to ear. "It's pink."

I left the exam room with a huge smile of my own. It's patients like her who make this profession rewarding beyond words.

When the clown stops laughing.

The death of Robin Williams has created a worldwide outpouring of sadness and grief that I have not often witnessed. Though we all know how closely linked depression and comedic skill can be, it is still difficult for many of us to fathom how a man that could have given us such great joy could have been so bereft as to kill himself. In Williams' case, it is made even more difficult because his humor was delivered impromptu, directly from his heart and soul. How does the playful, energetic, insightful man that we saw onstage become locked in such despair?

To understand, we need to look beyond the trope of the clown with tear-stained makeup and into the blackness that, to a certain degree, we all carry within. Just as there is no yin without yang, there is no joy without despair. But what is often overlooked is that the manifestation of depression is highly variable, and no two depressions are alike. Thus, we cannot approach their management in all the same way.

The death of Robin Williams has created a worldwide outpouring of sadness and grief that I have not often witnessed. Though we all know how closely linked depression and comedic skill can be, it is still difficult for many of us to fathom how a man that could have given us such great joy could have been so bereft as to kill himself. In Williams' case, it is made even more difficult because his humor was delivered impromptu, directly from his heart and soul. How does the playful, energetic, insightful man that we saw onstage become locked in such despair?

To understand, we need to look beyond the trope of the clown with tear-stained makeup and into the blackness that, to a certain degree, we all carry within. Just as there is no yin without yang, there is no joy without despair. But what is often overlooked is that the manifestation of depression is highly variable, and no two depressions are alike. Thus, we cannot approach their management in all the same way.

Some depressions are what I call "contextual depression." That is, they stem primarily from the your attempts to cope with a difficult, albeit temporary, environment. The loss of a loved one through death or divorce, an abusive work environment, severe financial stress -- all of these are situations in which depression begins as an appropriate adaptive strategy, but due to duration, or repetition, it becomes self-destructive and the behavior can continue long after the trigger that caused it has gone.

On the other hand, some depressions may have no obvious precipitating factor at all. This form of insidious depression works its way through you in the form of negative self-talk or the erosion of an impossible perfectionism slowly stripping you of, first, self-esteem, and eventually, hope. Not only is this depression subtle in its appearance to others, you may very well hide it from yourself until it has reached what may appear to be unmanageable proportions.

A third form of depression is a "physiological depression." This is a longstanding, moderate depression which does not have its origins in behavioral or neurological influences at all, but is instead caused by a chronic, debilitating and undiagnosed disease or infection, which in turn creates behavioral changes. Researchers who have watched the behavior of sick animals have noted that the symptoms of chronic, low-level illness are virtually identical to depression: Energy depletion, appetite changes, sleeping changes and behavioral changes which favor energy conservation and protection of vulnerabilities.

While the link between depression and health problems such as MS and back pain are well-known, often overlooked are diseases such as chronic gastrointestinal disease or gland hypofunction whose only visible symptoms are those of depression. Astute investigation on the part of the clinician is necessary to uncover these hidden causes of depression.

All of these forms of depression may be accompanied by substance abuse, creating a feedback loop that increases the severity and complicates the management of depression.

Too often, though, these various causes of depression are overlooked in favor of the cookie-cutter solution of pharmaceuticals. It is true that antidepressants can lift the veil of despair for some people, so the pharmaceutical solution cannot be discounted. But, as several meta-analyses of SSRI drugs have found, the effect of SSRI drugs is much smaller than we are led to believe. This is not news. The first such study was published over a decade ago. "Listening to Prozac but hearing placebo," examined 19 clinical trials incorporating over 2,300 patients, and concluded that SSRIs are primarily placebos.

"Virtually all of the variation in drug effect size was due to the placebo characteristics of the studies," the researchers concluded. "The effect size for active medications that are not regarded to be antidepressants was as large as that for those classified as antidepressants, and in both cases, the inactive placebos produced improvement that was 75% of the effect of the active drug. These data raise the possibility that the apparent drug effect (25% of the drug response) is actually an active placebo effect."

Several follow-up analyses have confirmed this initial study's findings. It is also worth noting that the monoamine theory of depression, which supposedly explains the mechanisms by which SSRI's work, has never been supported by the research.

So these drugs, while they can be invaluable for some people who suffer from depression, are more likely to be expensive placebos for the majority of people. What can you do if you are one of this majority?

The first thing is, see a mental health professional -- and by this, I don't mean a psychiatrist, whose primary skill is in pharmaceuticals, but a therapist, social worker, or psychologist, who can approach depression with a much bigger toolbox than that of the psychiatrist. They can help you develop the insight and skills to help you manage your depression.

Some of these skills include the ability to break down the monolithic wall of despair into more manageable chunks. Recognize and remind yourself that depression is a temporary condition, and you have the ability to influence how long it lasts. You can also reduce the size of your depression by converting generalizations about yourself and your life into specific, limited observations. The thought that "I'm a failure" creates an insurmountable hurdle to overcome -- after all, how could you, you're a failure! On the other hand, recognizing that generalization of failure stems from the fact that you lost your job creates a much smaller roadblock. You may have lost one job, or even several -- but that doesn't mean you cannot find another one.

One of the best ways to shorten the duration of a depressive episode is through physical activity. Though it may seem extremely hard, such simple things as going for a walk or a bicycle ride can change the course of the disease. Physical activity actually changes the neurological functioning of the brain in ways that inhibit depression.

And if you can't help yourself, what about helping others? Perhaps you can't find your way to feed yourself, but maybe you can help out at a food kitchen just a couple hours a week. Research has shown that when we nurture others, we also nurture ourselves. And if you are depressed, such sustenance is the best you can find. Helping others is true soul food.

There are many, many other ways to find your way through depression. And if you are thinking of suicide, reach out for help. It's there. Even if you can't find anything else, call 911.

Dr. Avery Jenkins is a primary care chiropractic physician specializing in helping people with chronic disease. He can be reached at alj@docaltmed.com.

The Doctor of the Future

Watching the news, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that humanity is fast approaching a turning point of great impact. I'm not speaking of ISIS or the Gaza-Israeli conflagration; conflicts such as this are older than history. Rather, I'm referring to the ever-growing polarity of our possible futures.

On the one hand, you have a rapidly growing income disparity and a civilization utterly dependent on cheap energy which is about to lose its primary source of that energy; a world that is already so overflowing with people that in even rich, technologically advanced countries, such basic things as readily-available water cannot be counted upon; a food supply that is so trucked-up in technology that it now causes the diseases that proper nutrition once prevented; and a worldwide ecology already in the midst of chaotic change.

Watching the news, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that humanity is fast approaching a turning point of great impact. I'm not speaking of ISIS or the Gaza-Israeli conflagration; conflicts such as this are older than history. Rather, I'm referring to the ever-growing polarity of our possible futures.

On the one hand, you have a rapidly growing income disparity and a civilization utterly dependent on cheap energy which is about to lose its primary source of that energy; a world that is already so overflowing with people that in even rich, technologically advanced countries, such basic things as readily-available water cannot be counted upon; a food supply that is so trucked-up in technology that it now causes the diseases that proper nutrition once prevented; and a worldwide ecology already in the midst of chaotic change.

On the other hand, you have technology so advanced that robots will soon be able to replace men in dangerous, life-threatening jobs, saving countless lives; the possibility, albeit remote, of extending mankind's territory to other planets; genomic manipulation to the degree that natural selection can be replaced with social selection, and entirely new species can be created; and artificial environments designed to replace the one that our overpopulation has begun to destroy.

The latter scenario is highly unlikely, except, perhaps, as a time-limited state in the longer progress of the former. We have already passed several points of no return in the alteration of our worldwide ecology, as CO2 levels have passed the 400 ppm mark, global temperature has reached the highest peak of this geologic period and shows no signs of stopping, and we are in the midst of a mass extinction of species. Our technology is nowhere near the point of replicating on any large scale, the vast diversity of the once-living earth, and that is critical to our survival at anywhere near our current population. Anyone who places their faith in unlimited technological progress in a reality circumscribed by limited natural resources is bound to be disappointed.

This shouldn't come as a surprise. From the beginning of history, civilizations have outgrown their habitats and outlived their creative energy, leading to periods of turmoil before another another order arises.

But the cry arises: "It will be different this time!"

Perhaps, perhaps. But not in the way the hopefuls imagine. The laws of physics and biology make it inescapable that we are headed for a post-industrial society of some sort. The only real question that remains is what that society will look like.

Certainly, the cheap transfer of goods and materials will cease. The days of raising chickens in the U.S., sending them to China for processing, and then shipping them back here to be sold will be long gone. With the disappearance of cheap energy, we will primarily be able only to move knowledge, not products, over long distances. Computational devices may remain, as they are less material- and energy-intensive, and can be supported by low-powered, decentralized power grids. Though they require exotic materials, they require them in small amounts, making their continued manufacture a possibility. Large-scale, centralized manufacturing will disappear, and if we manage our affairs right, we can arrive at a safe landing with local economies intact, using local resources for small-scale creation of goods. The post-industrial society, it turns out, will have quite a different flavor than the one first imagined by Daniel Bell, instead being closer to the future predicted by neo-Malthusians.

My interest, of course, is primarily in how this will affect health and health care delivery. A lot will change under this scenario, not all of it bad.

First of all, the changes in the transportation system will yield many positive results. With people walking and cycling more, obesity and many related sedentary lifestyle co-morbidities will greatly decrease. The incidence of diabetes, heart disease and cancers will drop significantly.

With energy-intensive factory farming techniques all but obliterated, a return to local production and harvesting of foods will further enable improved health through better nutrition. Indeed, a cultural shift in this direction has already begun, despite regulatory and economic roadblocks that have been put into place to protect the Monsanto-dominated paradigm.

A return to a more pastoral and village-centered lifestyle will also be accompanied by a decrease in the anomie of life that is a direct outcome of our currently disconnected, disembodied and overly-embroidered lives. Less depression and anxiety almost always accompanies stronger social networks.

Of course, all of this is predicated on the maintenance of a society relatively protective of both individual liberties and cognizant of the need of our strong social obligations to one another. And it's not all sun-dappled rides on two wheelers through abundant fields of grain, either.

Drug production and distribution will be inhibited, putting those dependent on such drugs, such as insulin-dependent diabetics, at risk. Essential vaccines, such as pertussis and measles, would become scarce. And antibiotics, which are already on the wane would be hard to come by, though as I have previously mentioned, that's not necessarily much of a calamity. Certainly "advanced" medicine, with its exotic potions and technology-dependent surgical techniques, will go by the wayside.

I'll make the argument that, in fact, much of that medicine and technology is largely superfluous. The advanced medicine of the latter half of the 20th century and the first decade of this one has made no impact on human longevity, measured in productive years. Many of the surgeries and medicines that are employed today are only necessary because of the society in which we live. Change the parameters of that society, and these disorders would largely cease to flourish.

What does that leave us with, health-wise? It leaves us with a health-care delivery system which is supported by locally-available resources, and which utilizes low-technology manual interventions. It would also leave us with a health care system supported by a truly interdisciplinary population of healers, unrestricted by practice laws and insurances aimed more at preserving the power and income of a protected class of professionals.

In this health care milieu, there would be more shamans and crones and fewer psychiatric wards, more midwives and fewer cesareans. There would be doctors who know the properties of herbs, where they could be found, and how they could be prepared. Who know the use of food and nutrition to turn on the genes of health. Who know foodstuffs and how to use them to cure disease, and who know the human body and its anatomy, and who can alleviate pain with their hands. Doctors who can continue to work when the lights go out.

The fact of the matter is, the doctor of the future looks very familiar. And as I more frequently walk upon the Old Paths in search of the knowledge that can help my patients, I am increasingly cognizant that the wisdom I gather is not only for the benefit of my patients today, but also for the doctors of the future.

Diseases are just stories we tell ourselves.

Recently, I was explaining to a patient the difference between her diagnosis from a western mainstream doctor, and the diagnosis I had just given her, which emerged from an examination based in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).

Recently, I was explaining to a patient the difference between her diagnosis from a western mainstream doctor, and the diagnosis I had just given her, which emerged from an examination based in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).

"Diseases are cultural concepts," I said. In mainstream Western medicine, certain symptoms, signs, and laboratory tests are grouped together because it makes sense to congregate them given that view of the body. We clump that fact pattern together, call it a disease, and give it a name. Eastern medicine may likely have no analogue, not because the disease had not been "discovered" by TCM doctors, but because when looking at a person from an Eastern perspective, it makes no sense to clump those findings all in one pile; in TCM, some go in one pile, and some in another, and neither fully replicates the Western diagnosis.

Which is a good thing. One of the greatest failures of western medicine (aside from its obeisance at the altar of Mammon) has been its failure to recognize that a disease is not a creation of biology -- it is a creation of culture.

On the personal level, a disease is, in fact, a story we tell ourselves about ourselves. It is one of the many myths we use to make sense of our lives, to collate and correlate all of the data we collect into a coherent whole, a narrative that relates ourselves to our world sequentially in time and which gives meaning to our lives.

From this perspective, then, it is the doctor's job to provide the story in which the patient immerses themselves. Our important knowledge base is less one of laboratory values and abstruse structures on x-ray than it is the particular narrative in which which each patient can find association.

For example: If I tell a patient that they have arthritis, without any qualifiers, their reaction can vary tremendously. This is because of the associations which that word has in their mind. One patient may immediately think of rheumatoid arthritis, which erodes joints and may leave its victims disabled and wheelchair-bound, fighting constant pain. Another patient may assume I'm referring to osteoarthritis, the wear and tear of joints which eventually effects us all, and may only display as some stiffness and a mild loss of range of motion. I can watch, physically, as they respond to their interpretation, sinking into themselves in resigned defeat or shrugging their shoulders as if to unburden themselves of a fly. Each patient is telling themselves the story which they will be living, and reacting accordingly.

Most people these days are familiar with the concept of a placebo -- a physiologically inactive intervention, such as a sugar pill, that a patient takes and it miraculously begins to heal them. Placebos can be extraordinarily powerful interventions, to the extent of curing people of cancer. The key aspect of the placebo effect, though, is that the patient cannot know that they are taking a placebo.

The cause of the placebo effect is that it is an item that a person can use to change the sequence of their narrative. To understand how that can be so, we must first take a shallow dive into Jungian psychology and the realm of mythology. Joseph Campbell, in his book The Hero With A Thousand Faces, describes what he calls the "monomyth." This is the tale of the hero, who leaves his safe home, fights monsters and giants, faces death (and dies), and then returns to his world and his home as a more complete (healthier) individual. This is a story that exists or has existed in virtually every culture over mankind's history, and regardless of the time, culture or language, all of these heros' journeys have common elements.

This is the journey of individuation that we all undertake during the course of our lives, and it may be a trip that we take several times in several ways. The hero's journey is also the path that many people follow when faced with a disease. I have seen patients replicate this journey many times over the past 20 years, and the pattern I have observed hews closely to the Campbellian outline.

There are several stages in the monomyth. The first is the "call to adventure," which in a clinical setting is best seen as the time of diagnosis. The hero (patient) often resists this call (denies the diagnosis), but after rising to begin his or her journey, one of the first encounters that our hero has is with a supernatural or magical helper, who often gives the hero a talisman or artifact that will aid him in his quest. Again, in the clinical context, the supernatural helper is the doctor (or magician, shaman or priest in other cultures), and the talisman in this culture is most likely to be a pill, herb, or chiropractic adjustment.

The exact nature of the talisman is unimportant, as is the factual existence of the powers that it is claimed to possess. What is most important for the hero (patient) is that "protective power is always and ever present within or just behind the unfamiliar features of the world. One has only to know and trust, and the ageless guardians will appear," Campbell states.

This is the power of placebo, and indeed, this is part of the power of every therapeutic intervention, regardless of its physiological properties. In fact, in the case of many interventions, the physiological properties are far weaker than the magnitude of its therapeutic effects. But because these are talismans imbued with protective properties, given to the patient by a figure representing a force stronger than their own, their power is magnified.

What the drug/herb/adjustment is really doing, far more important than chemical or mechanical changes, is giving the patient the power to change the outcome of their narrative. The feared enemy is no longer stronger than the hero and their playing field is now levelled.

Thus, the outcome can be changed, literally, in the patient's mind.

This approach -- seeing the disease process as a story we create, or co-create with our environment, is hardly a novel or new one. It is, however, a largely forgotten one, in a day and age when diagnosis is based primarily on laboratory testing rather than observation and interaction with the patient.

For patients, this realization that our diseases stem, to a great degree, from how we interact with our internal and external worlds can be an initially frightening revelation. One might accuse me of cruelty to suggest that a person with cancer, or heart disease, or even MS, is in some way, responsible for their disease. My words, though, are less the whip of admonishment than they are a call to hope.

Taking responsibility for something is the first step in being able to manage and control it. If a disease is declared genetic (the scientific version of "an act of God"), it becomes something impossible for the patient to overcome, because, who, after all, can defy the almighty Gene? (This approach, by the way, is also a very good way to deify the doctor for his own benefit, but that's a tangent for another day).

If you can claim ownership and responsibility for a disease, then you are simultaneously reclaiming the capacity to change it's course. You are changing the narrative of your disease. You are changing from victim to hero.

Of course, that alone isn't enough. You have to change whatever needs to be changed, behaviorally, mentally, emotionally, in order to change the actual course of your disease, and the talisman given to you by your doctor will only help you so much. The rest you must do yourself.

Any disease, your disease, is just a story you are telling yourself. And whether the outcome is tragic or triumphant is entirely up to you.

Hey, Dad!

Two simple words that for nearly two decades I have been unable to speak. Two words that, for much of my life, prefaced any number of of statements and questions, from the sacred to the silly to the profane. The two words that reflected one irrevocable fact that shaped my life more than any other. I had an awesome Dad.

And, as a man, in many ways I am just like him. My father was an engineer who liked to tinker with things, figure out how they worked, how they broke and how to fix them. I cannot remember ever having a repairman in the house. I, being the only child with any aptitude for such things, became his gopher (as in, "Avery, go for a phillips head screwdriver") and learned by observation, as children do. I learned how to rewind transformers, fix a faulty TV, wire a house electrical circuit and fix a toilet. Dad hated fixing toilets. Which is probably why ours broke down so often.

Two simple words that for nearly two decades I have been unable to speak. Two words that, for much of my life, prefaced any number of of statements and questions, from the sacred to the silly to the profane. The two words that reflected one irrevocable fact that shaped my life more than any other. I had an awesome Dad.

And, as a man, in many ways I am just like him. My father was an engineer who liked to tinker with things, figure out how they worked, how they broke and how to fix them. I cannot remember ever having a repairman in the house. I, being the only child with any aptitude for such things, became his gopher (as in, "Avery, go for a phillips head screwdriver") and learned by observation, as children do. I learned how to rewind transformers, fix a faulty TV, wire a house electrical circuit and fix a toilet. Dad hated fixing toilets. Which is probably why ours broke down so often.

I translated that talent for fixing what's broken into being a doctor. Helping to fix a person is infinitely more complex than diagnosing and repairing a major appliance, but the fundamental mental processes are the same. Questioning, observing, probing, changing something to see what happens -- this is what he taught me. This is what I know.

Dad also had a philosophical bent. When his lifelong employer, AT&T, moved Dad into an executive track, they also sent him back to school. At the time -- the late 50s -- AT&T was promoting many engineers into management, and they saw that the engineer's traditional tech-only training was insufficient to prepare these men for the more complex task of managing people rather than managing circuits. So they created a special one-year school in Philadelphia, where these electrical engineers were submerged in the works of Plato, Kant and Kazantzakis. They studied art, they read literature, they explored classical music.

Dad absorbed it like a sponge, and transmitted that love for the big picture to me. I will always remember our "Culture Hour Sundays," in which Dad would play some music and talk about the composer, or introduce a Big Question, like "Who are you?" and make us discuss it. I thought it was all pretty silly, as a child. But it clearly rubbed off onto me, as I went to a college in which I studied things like the similarities between Cubist art and Einstein's theory of relativity, and read Kant, and Hannah Arendt, and tried to answer the Big Questions, like "Who am I?" I graduated with a Bachelor of Philosophy degree. Dad was proud of me.

Dad was, by his own description, "the man in the gray flannel suit," one of the army of men who, after returning from World War II, went to work in the companies grown large by the demands of the war and changes in technology, and became cogs in the machine of extraordinary economic progress that was America after the war. He was a corporate man, learning to work his will in a bureaucracy unyielding to personal intent.

But within him seethed a man wanting to break free of that bondage, to create that what he would, to be master of his own fate rather than one hand of many on the tiller of a great ship. Somehow -- I have no idea how -- he snuck that into me. In spades.

This was my father's greatest gift to me, or perhaps it was a curse. I'll never be sure. But it became clear to me early on, that I would never become the baby boom generation's version of the corporate man. I was too infected with Dad's questioning spirit and his suppressed demand for independence. I realized in my 20s that I would never be happy working for anyone beside myself. So one day I closed the door on my own budding career in management and decided that I would make it on my own or not at all.

As a father myself, I have tried to emulate my Dad as much as possible. It's still a little too early to tell how I did on that score, but I'm sure my girls will let me know. One has already launched and is, as I write this, achieving orbital velocity. The other is moving inexorably toward the launch pad, and already my heart grows heavy with her impending departure.

When I graduated high school, my parents gave me two gifts which have lasted me a lifetime. The first was a typewriter, through which I found my voice and which was the heart of my first career. The second was a train ticket to Boston, the city in which I found my destiny and that eventually became my second home.

I will never forget, the day after my last class, looking out the window of that train, and seeing my father with tears running down his cheeks and a huge smile on his face as he waved goodbye to his son. Many years later it was my turn to say goodbye, as I held his hand and looked into eyes rapidly fading as a the hemorrhage caused by a massive stroke flooded his brain like a a slow tsunami. I, too, had tears in my eyes and a smile on my face for the man who had given me so much -- had given me the core of the man I had become.

Hey, Dad, thanks for everything. As long as I live, so will you.

I Am Biped.

Inspired in equal parts by laziness, a fondness for offbeat experimentation, and personal growth, I have been walking to work for the past two months. It's not a very long commute by any standard, a pinch less than a mile, although the 8% road grade is relatively indisputable and I can't quite decide if it is in the wrong direction. As things stand now, I have a sprightly downhill jaunt in the mornings, and an uphill slog at the end of the day. And since it's so short, I've been walking home for lunch as well. Sometimes I insist that the directionality, or at least temporality, of the slope be changed, but at other times it seems perfectly fine. I suppose with regard to the kerfuffle that is local geography, the gods in fact do know their business, and I should leave well enough alone.

I started foot commuting by fiat one morning, when bike #1 had a flat tire and Bike #2 was on the repair stand for cable replacement. (Of course, I also have bikes #3 and #4, but we really needn't delve too deeply into my transportational quirkiness here). I have a difficult time justifying using an automobile for such a short distance, unless I'm coupling it with other errands. To me, such sloth smacks of an immorality commensurate with unfiltered Chesterfields, pool halls and Hudepohl beer. It also hasn't been that long since I finished reading The Old Ways, a book about walking the ancient paths of the U.K., which seeded my mind with the desire to see what a walker sees and experience the world from a walker's perspective. So I slapped on my office clothes and perambulated my way to work.

Inspired in equal parts by laziness, a fondness for offbeat experimentation, and personal growth, I have been walking to work for the past two months. It's not a very long commute by any standard, a pinch less than a mile, although the 8% road grade is relatively indisputable and I can't quite decide if it is in the wrong direction. As things stand now, I have a sprightly downhill jaunt in the mornings, and an uphill slog at the end of the day. And since it's so short, I've been walking home for lunch as well. Sometimes I insist that the directionality, or at least temporality, of the slope be changed, but at other times it seems perfectly fine. I suppose with regard to the kerfuffle that is local geography, the gods in fact do know their business, and I should leave well enough alone.